Relational Field Theory

It’s Not Actually All About My Dad — It’s Just a Lot About My Dad

Origin Story from the Platte River Basin

People keep assuming my work is “about my dad.”

And sure — a lot of it is.

How could it not be.

When you lose a parent young, the absence becomes a kind of weather system you grow up inside.

It shapes your seasons.

It shapes your instincts.

It shapes the way you listen for danger and the way you listen for love.

But here’s the truth I didn’t understand until much later:

My origin story isn’t actually about my dad.

It’s about a river.

The Platte River — shallow, stubborn, shifting, impossible to contain — is the real ancestor in this story. The real teacher. The real architecture under everything I make.

I didn’t know that until I stood on its banks as an adult, long after the grief had calcified into something I thought was “just my personality.” Long after I’d learned to survive by being small, quiet, adaptable, watchful. Long after I’d forgotten that I came from a place where the land itself refuses to move in a straight line.

Several years ago, I was a non‑traditional student at Western Wyoming Community College. I’d been accepted into the Honors Colloquium, which meant I had to take an “Intro to Natural Resources” class with a professor who was brilliant, dry as sagebrush, and somehow both compelling and allergic to enthusiasm. The class was fine. The field trip changed my life.

We went to Grand Island, Nebraska — to the Crane Trust on the Platte River.

If you’ve never heard 600,000 sandhill cranes wake up at once, you don’t know what volume is.

It’s not sound.

It’s a force.

We got up at 3 a.m. to sit in the blinds. Every other student complained. I was vibrating with anticipation. I watched the river breathe. I watched predator arcs in the dark. I watched the cranes shift like a living continent. I watched a system so adaptive it didn’t fight its obstacles — it flowed around them.

And something in me recognized itself.

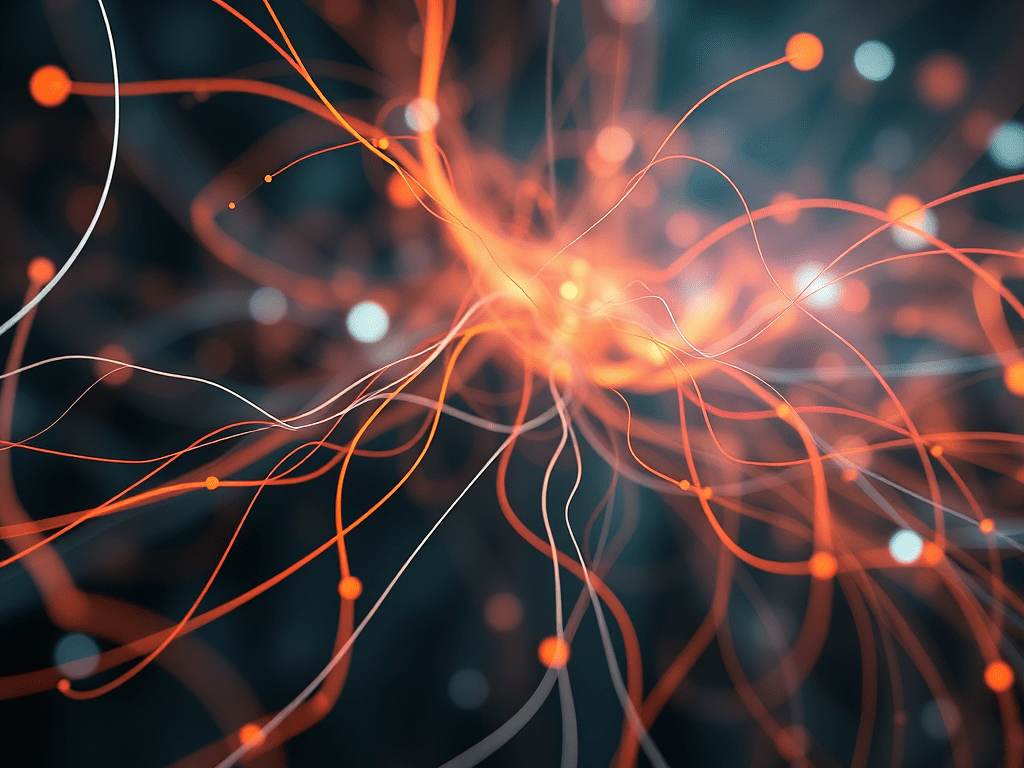

Because the Platte isn’t a “normal” river.

It’s a braided river — a network of channels that split, rejoin, wander, reshape, and refuse to be pinned down. It’s shallow but powerful. Quiet but relentless. It doesn’t carve a canyon; it negotiates with the land. It doesn’t choose one path; it makes many.

Standing there, I realized:

This is me.

This is how I move.

This is how I create.

This is how I survive.

My maternal family comes from that stretch of Nebraska — Hershey, Sutherland, North Platte. I grew up thinking that was just trivia. But it’s lineage. It’s hydrology. It’s the watershed that shaped the people who shaped me.

I thought my story was about loss.

But it’s about water.

I thought my story was about grief.

But it’s about movement.

I thought my story was about my dad.

But it’s about the river that held the land that held my family that held me.

I belong to the Platte, and the Platte belongs to me.

Everything I make now — the multilingual songs, the ritual pieces, the sideways expansion, the refusal to fit inside a single genre or identity — is just the river moving through me. A braided system doesn’t apologize for having many channels. It doesn’t collapse itself to make other people comfortable. It doesn’t shrink to fit a box.

It flows.

It adapts.

It survives.

It creates new land as it goes.

My dad is part of the story.

A big part.

But the river is the origin.

And I’m finally letting myself move the way I was always meant to — not in a straight line, but in a braid.

What do you think?